|

|

A Short Account of the English Concertina, …

|

|

|

|

|

Posted 15 January 2005 A Short Account of the English Concertina,

|

Entered at |

Stationer’s Hall |

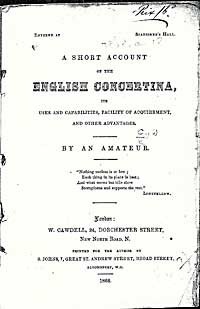

A SHORT ACCOUNT

of the

ENGLISH CONCERTINA,

its

Uses and Capabilities, Facility of Acquirement,

and Other Advantages.

BY AN AMATEUR.

“Nothing useless is, or low;

Each thing in its place is best;

And what seems but idle show

Strengthens and supports the rest.”

Longfellow.

PRICE TWOPENCE,

will be sent by post on receipt of three stamps.

LONDON

W. CAWDELL, 24, DORCHESTER STREET,

New North Road, N.

Printed for the Author by

S.Johns, 7, Great St. Andrew Street, Broad Street,

Bloomsbury, W.C.

1865.

[p.2]

[Blank.]

[p.3]

To the Reader.

The motives that induced me to present you with this little work spring from a firm opinion that the cultivation of Music at home is an elevating recreation calculated to enlarge the mind by administering to the imagination the purest delights, and that the English Concertina is an instrument the least difficult to learn combining all the advantages of a Keyed Instrument with the greatest powers of expression.

That very different ideas prevail on this subject is evident from the following extracts:

The Orchestra, May 6th, 1865. In a letter to the Editor on Concertina Concerts, may be read the following words: “the worthiness of the Concertina to be accorded a position in the performance of classical works, where it maintains its voice-like beauty of tone and charming versatility, now alternating, now harmonizing with other instruments, differing from yet admirably blending with them all.” … … “An instrument worthy of cultivation, not only by way of a domestic luxury, but also in amalgamating with any other instrument in the interpretation of orchestral music of the highest order.”

A very decided contrast to the above is offered by a passage in the Pall Mall Gazette of 1st June, 1865. under

[p.4]

the head of Herr. Molique's Concert. “Signor Regondi astonished and almost amused the audience by playing a surprising fantasia on the Guitar of all instruments in the world … … many of the effects were quite as pleasing as those of the modern musical toy, Mr. Regondi’s own more notorious Concertina.”

Having some experience as an amateur, and with a view to supply certain facts which may be valuable to some though not generally known, I confidently launch my little skiff on the waters of publicity, hoping for the fair winds of your good opinion to ensure a pleasant voyage.

W.C.

London, December, 1865.

[p.5]

The Concertina.

There exist many reasons why a fair and earnest inquiry into the merits of the Concertina at the present time should be acceptable, of which I will merely instance the following:—

Firstly.—The increased opportunities of hearing good music, and the facilities of acquiring a little knowledge of Musical Science, now accessible to all.

Secondly.—The many disadvantages which prevent the instrument in question from being much known, arising partly from the modern date of its invention, and partly from the circumstance that while eminent Professors of the Concertina obtain not only the credit due to their performance, but much also that belongs of right to the instrument, the faults, on the other hand, of indifferent performers are not so readily perceived, and all their shortcomings are placed to the account of the Concertina.

the incorrect notions generally prevalent on this subject first induced me to examine the qualities and advantages of this domestic and portable instrument, in analysing the character of which we shall find that it exhibits a peculiar fitness for elucidating the general principles of harmony, thus materially

[p.6]

lessening the Labours of the Teacher and making up for any deficiencies on the part of the learner with respect to the faculties exercised in the study of Music. Notwithstanding its modern invention, and the fact that inferior imitations have caused the Concertina in its perfect form to be comparatively little known yet wherever introduced it has been cordially appreciated on account of its sweet one, facility for correctly rendering passages of sustained notes as well as harmony, and power of expression, however varied. It is portable, and adapted to every style of composition, blending with other instruments or making a delightful addition to Vocal Music. There are Concertinas of varied compass and description, Treble, Tenor, Baritone, and Bass, which may be tuned to equal or unequal temperament and to any pitch that may be desirable; indeed, connoisseurs frequently have several instruments of different pitch and quality of tone, and sometimes more than one set of notes to the same instrument, an arrangement which affords advantages unobtainable by any other means and of incomparable value under certain circumstances. Music written for any other instrument can be performed with ease on the Concertina in addition to that composed or arranged specially for it.

We cannot expect enthusiasts in favor of other instruments to admire or praise the Concertina, which however possesses sufficient good qualities to recommend it either to the Professor or the Amateur, and only requires to be heard under favorable conditions in order to furnish a complete answer to any objections arising from prejudice or inexperience. To argue on matters of taste would be vain indeed, but I will venture to assert that a modern and popular instrument elegant, and easy to learn, is worthy of receiving more attention than is at present

[p.7]

accorded to it, and I trust you will not condemn me for taking upon myself the office of champion to combat such erroneous opinions as still exist centering on the Concertina, although the increasing number of patrons, and greater opportunities of being heard at Concerts, are gradually obtaining for this instrument a certain amount of recognition.

The attention of Professors is to a great extent devoted to the exercise of their practical skill, and perhaps any attempt on their part to extol the merits of the instrument they profess would only be tolerated on account of the excellence of their performance: I am, therefore, convinced that it is to Amateurs we must look for the verdict as to the title of the Concertina to popularity and favor, and it is in the capacity of a disinterested and unprejudiced amateur that I am desirous of giving such definition of it as I am able. As a piece of exquisite workmanship there is sufficient to interest one in the simple yet elaborate details, strength combined with elegance in all its parts, and symmetry with completeness in the finish. Whether we consider the number of its component pieces, the various kinds of material used, or its compact and handsome appearance as a whole, to say nothing of the intricacies connected with securing correct tone, and perfect action, we cannot help admiring the combination of industry and ingenuity required for its production as well as the science and skill displayed in its original invention.

It is now about thirty-six years since Professor C. Wheatstone invented those improvements which called forth a new instrument from such principles as were already extensively used in many foreign countries and well known in this, viz. the action of the air on vibrators attuned and arranged for the performance of the scale with more or less accuracy and precision. These im-

[p.8]

provements consisted principally of such arrangement of the finger keys or studs of a certain size as would without preventing free action when using them singly yet allow of the pressing down of two or more with the same finger and at one time: also the close proximity of semitones making modulation into different keys quite easy, and lastly the double action which entirely does away with the necessity for a valve, and allows of the greatest rapidity of utterance. Having gone thus far, we find many other advantages springing from these, for a good work honestly undertaken generally obtains higher results than were at first attempted or even anticipated.

These other good qualities have reference to the practice of harmony, to explain which I must speak just a little technically. Not only are thirds, fifths, chords and octaves found in the readiest manner but the dominant is really over the key note, and the sub-dominant under it: illustrating some of the rules of Musical Science as perfectly as if the position of the keys had been taken from the diagrams in some theoretical works on the formation of chords.(1)

This conformity of principle in the musical instrument and technical definition of the formation of chords, triads, &c. reminds me of the lines of Pope:—

“Those rules of old, discovered not devised,

Are Nature still, but Nature methodized;

Nature, like Liberty, is but restrained

By the same laws which herself ordained.

(1) Those who understand Music will observe how the notes of the chords of the Subdominant, Tonic, and Dominant are placed: C E G Tonic, F A C Subdominant, G B D Dominant. Also the progression, C to G, G to D, F to C, &c.

D

B

G

E

C

A

F

[p.9]

In very many ways we find the Concertina illustrate the scientific rules of Musical theory; for instance, the scale of nature (as it is sometimes called) distinct and complete, the ascending and descending according to the pitch of the note;(2) the semitones conveniently close for those passages where the particular effect requires their use, as also for modulation or change of key; besides which, many facilities will present themselves to the musical student for illustrating passages as they occur in his reading whether of ancient or modern idioms, or examples harmonized; as it is of great advantage, while the argument which accompanies any particular phrase is fresh in the memory, to be enabled to try the effect of the example given to aid the study and correct understanding of the subject still in view, before our interest in it is allowed to die away. In the consideration of those qualities which make the study of Music so easy I must not forget to mention that there are two extra notes in the scale greatly facilitating accompaniment in different keys, and it is also worthy of notice that throughout the whole scale of the Concertina, the keys corresponding to notes placed on the lines of the musical staff are on that side of the instrument touched by the left hand, and of a consequence the notes occuring in the spaces are all played by the right hand. (This is easily remembered as the letter l begins the word left and also lines.)

The Red Keys like the Red Strings of a Harp are used for the key note (c) of the natural scale, and although this is a mere arbitrary rule (indeed the better kind of instruments have the keys all alike) it is remarkable that in the old Latin Nemna, a method of writing music older than the Gregorian chants

(2) Some persons erroneously imagine that the high notes are played by the right hand and the bass by the left.

[p.10]

differently colored lines being used for the tonic and subdominant the scale of c was marked by a red line. From the peculiarities I have enumerated and the simple manner of producing a sound which may be increased or diminished at pleasure as well as making a succession of notes form either a smooth and flowing or a distinct and emphatic passage, results the fact that the Concertina is the very easiest of all instruments for the learner, a fact worth remembering in the present age of progress and refinement when a love of Music and a general knowledge of its principles daily celebrate fresh triumphs, enlisting a crowd of recruits devoted to the cause. But while we praise and encourage Music are we really doing all we can to cultivate the pursuit? Might we not increase the practice of social and domestic Music in the higher branches of the art, symphonies and concerted pieces which require the development of other faculties than the ability to execute brilliant fantasias and intricate variations? The latter exhibit manual dexterity while the former appeal to the sensibilities and cannot be realized in their integrity, without a deep and earnest love for true Music. Should any one be inclined to think it absurd to mention Concertinas and symphonies in the same breath, I beg to inform him that not long ago, I assisted in the performance of an Overture by Amateur Concertinists, and I have before me a Programme of a Public Concert, where Professional Artistes performed operatic selections and fantasias arranged for four and five concertinas, such as two trebles, tenor, baritone, and bass.

I am well aware that the indiscriminate introduction of Music into every transaction of our daily live would be incompatible with our ordinary pursuits and on the whole undesirable, but if its practice cannot always be indulged in, its effect may

[p.11]

nevertheless be continually apparent in the regularity of our actions, and precision of our ideas, and not one in twenty is so intensely occupied as to be unable to spare a few minutes a day to be devoted to this refining pursuit. Perhaps some of you may imagine that a few minutes’ leisure would be of very little use: true! if your aim be mere tours de force in the dexterous manipulation of any instrument, your ambition bounded by the wonderful execution of difficult pieces; but for the enjoyment of real Music by entering into its spirit and cultivating sympathy with its many harmonizing qualities you will find that far less time is required than you at first supposed; less than is bestowed by many in qcquiring an appreciation of a good Havannah or ability to enjoy the glorious vintage of Champagne. The fact is the less we do, the less are we inclined to do, and the more we do, the more we find we can do.

Music has but one mission, our improvement, although it attains this end by various means. The music of the Church fosters devotional feeling in the Soul, and intensifies the influence of solemnity of worship. The Music of the Concert-Room improves the mind, feeding the intellect by offering to our contemplation the chef-d’œuvres of genius and labors of giant minds. The Music of the Home more directly appeals to the heart fostering the affections and encouraging noble sentiments. It is in this particular that the Concertina will be found a most useful co-operator in the cultivation of an elevating recreation that will enlarge the mind, purify the affections and strengthen the intellect. It is more directly as a domestic instrument that it is and ever will be appreciated and admired, although it will also be found with more cultivation, eqully eligible for other uses such as concerted and orchestral pieces.

[p.12]

I must now run over some of the qualities of this instrument, the combination of which makes it so well adapted for amateurs desirous of cultivating Music in an efficient manner, meeting the necessities of those who commence the study late in life and also the shy individuals who my fear to attack such an instrument as the Violin, whether from the difficulties of the task, or a modest estimate of their own capabilities.

Firstly, it is most admirably fitted for interpreting every kind of Music whether simple or elaborate, capable of the greatest expression, and some ornamental flourishes and embellishments peculiar to itself. Then the simplicity of the fingering enables the learner after very slight practice to perform a regular scale ascending or descending throughout three octaves and a half simply by the progressive motion of the first and second finger of each hand alternately, and this with far greater rapidity than could be acquired on any other instrument with twice the amount of application.

Again, having a perfect chromatic scale, there is no necessity for the ordinary player to transpose or re-arrange Music written for any other instrument, while the two extra notes in each octave make it easy for playing in seven or eight different keys (and even the remote ones are not so awfully difficult) to say nothing of the tuning, say to unequal temperament, preferred by many connoisseurs and singers, an advantage that was considered of some value when the Temple Organ was built for that (like our friend Concertina) has different Notes for D sharp and E flat, as well as for A flat and G sharp.

The contest of the players on two organs differently tuned having already been made the groundwork of a great deal of

[p.13]

controversy as to the superiority of tweedle-dum over tweedle-dee, I will considerately pass it by.

The chords are easily touched on the Concertina, and the progression from the dominant seventh to the tonic (marking a full cadence) without shifting the position of the hands: and scarcely perceptible are other shifts very difficult on some instruments.

The notes are all easily produced and sustained, so that the practice of beginners need not be excessively disagreeable to others, in striking contrast to the Flute, Clarionet, Violin or even Cornet if played in the house.

Its portability is another advantage strongly recommending it to persons going a long voyage, or young men not settled down in life, perhaps using only a small room, their movables contained in a single box. A Piano would be out of the question for them.

Then again the Concertina may be played in any position, standing, sitting, walking, kneeling, or even lying down. If confined to the house by a sprained ankle, you may play whilst reclining on the sofa, it will soothe you to forgetfulness of the pain; and when you are convalescent, you may take your instrument into the fields where the Piano can never be. If my almost namesake, Job Caudle, had been possessed of a Concertina he might have escaped many a Curtain Lecture. For a number of years the enjoyment of this kind of Music was confined to a privileged circle, beyond which it received as much ridicule as favor, partly owing to an inferior imitation made abroad and much patronized by street boys, and partly to the fact that it has been regarded as fit only for a parting

[p.14]

present to some cadet fresh from Sandhurst about to embark for India who might in the retirement of his bungalow at Muddle-a-poor-head, learn to draw out the notes of “Home! Sweet Home,” while yearning for the realization of the idea. It might be admitted at a river pic-nic, such as Mr. Wilkie Collins has described in his story of Armadale (see Cornhill Magazine for June, 1865) where young Pedgift introduces his Concertina with the remark “I sing a little to my own accompaniment.” The offer made my him to “play a running accompaniment impromptu if the singer would favour him with the key note” appears to me to classify it as an English Concertina although if farther proof were requisite, it is supplied by the statement the “it still flourished and groaned in the minor key.”

I have never had the pleasure of hearing Signor Regondi, but I will here give the sentiments of a correspondent of the Orchestra, in a letter to the Editor published in the No. for 29th April, 1865, “It is impossible to overlook the claims of Signor Guilio Regondi, who is incomparably the finest performer on this instrument, and who, indeed, first made it known to the public as thoroughly effective for the expression both of melody and harmony. To me the playing of Regondi realizes the perfect mastery of an accomplished performer where the idea of mechanism is lost sight of, and the instrument, like a well trained voice, becomes entirely subservient to the present feelings and inspirations of the musician.

Similar praise is heard on all sides of this excellent artiste, and allowing him to be the centre and brightest star in this department of the Musical Art, we may nevertheless learn what is said of others who are walking in the path that he has first traced out. For instance very much commendation has been

[p.15]

bestowed on the performance of Mr. Richard Blagrove, and recently on that of Mdlles. Lachenal, who gave a popular Concert at Islington in June last, noticed by a local paper (the Islington Times) in the following words:— “the Mdlles. Lachenal’s Concert is we believe the first entertainment available for the million in which the Concertina has been in a position fairly to challenge a verdict on its merits as an orchestral instrument of surpassing beauty and extensive capabilities. The Concert commenced with an operatic selection for five Concertinas (two trebles, tenor, baritone and bass), of which the united effect was magnificent, now resembling the tones of an organ, now more like to a string band, preserving the spirit of the airs, yet gracing them with a novel charm.........Madlle Marie Lachenal was deservedly encored after performing a splendid fantasia on the airs from “Faust” on the Concertina with great taste and artistic effect; this one piece was sufficient to entitle the Concert to a success but the enthusiasm of the audience rose higher still on hearing a trio of Scotch airs for treble, baritone and bass Concertinas by the Mdlles. Lachenal.........the performance gave evidence of much talent and finished style and the Concert successfully demonstrated to the general public that which was known only to a few enthusiastic amateurs—viz., the adaptability of the Concertina to first-class orchestral Music, where this elegant instrument shines with peculiar effect both in melody and harmony, and sustains the full score unaided by instruments of any other description.”

In taking leave of the subject for the present it is well to observe that although the Tonic Solfa system and the exertions of Mr. Hullah have done much to make all classes familiar with some of the best compositions both ancient and modern,

[p.16]

there is still an unsatisfied desire for sweet music in many families where the members think that some special gift is necessary for practical Music, (if not genius, at any rate talent) and that training only brings out the capabilities they already possess; now, my own opinion is this, that with a love of the art and a quiet perseverance, any one may advance to a very fair average ability of performance; for, after all, it is practice which makes the fingers pliant, and our ears are as susceptible of education as our eyes. A forcible illustration came under my notice lately: a professional gentleman has established a class for the practice of concerted Concertina Music in the neighborhood of Islington, and it is astonishing in how short a time several pupils quite fresh to Music of any kind were able to take part in very capital performances. A person commencing to learn an instrument can give no satisfaction to his hearers until he has acquired some little proficiency, and he is far more likely to arrive at success by taking a subordinate part with others, for by listening to good Music his taste will be improved, and if the study of Harmony be persevered in, it will be better understood and valued.

In detailing my experience of an instrument which has opened the gates of the Palace of Harmony to many, who but for its aid, must ever have remained outside, I have purposely avoided anything like an explanation of how to play, as belonging to quite another province; the many excellent instruction books published, offering ample choice to the purchaser. Although the Concertina may seem at first sight particularly adapted to the Solitary, it is equally favorable to the most social occasions, such as festive parties, whether musical or terpsichorean: for myself, I frequently take my instrument

[p.17]

with me when visiting my friends; and for playing with the Pianoforte, I usually take the melody, but, on the contrary, if my companion should play the Violin or Flute, I leave him the melody, and play under, at one time full chords, at another a running accompaniment. In concerted Vocal Music, you may, with a Treble Concertina, take first or second line, or accompaniment according to taste. I must not omit to speak of lady concertinists; I have heard of the dangers of Croquet to young men of a susceptible turn of mind, but I think that those perils cannot be compared to the fascination of a group of young ladies in a magic semicircle practising selections on several concertinas. I remember once being present at such a scene, and I went home suffering from heart affection and Concertina on the brain combined. I recovered entirely from the first, but the effects of the latter have not quite disappeared. Ecce signum in hoc libro.

The purchase of an instrument requires a little judgment, and a novice should, if possible, have the advice of one who is used to play. Of course a thorough good Concertina is cheaper in the end. But having obtained your instrument, two faults at starting must be carefully avoided; the first, drawing or pressing the bellows without touching a note: the second, jerking or snatching suddenly when the note is touched; for by either of these malpractices you may injure a good instrument. A great advantage will be derived from learning the written music early, so as to allow of the eye keeping a little in advance of the fingers: experience will prove the observation of this rule to be of much service in obtaining facility of performance, and leaving you more scope for expression. A ridiculous mistake is fallen into by many persons, in laying in a stock of

[p.18]

music, and running from one piece to another, having the very opposite effect to the one they desire, that is, of bringing them on quickly: a beginner should confine himself to a few simple melodies, until he has learned to play them tolerably well. Others are perpetually anxious to change their instrument; they should rather improve their playing by continued practice, for patience is required before they can hope to succeed. The instrument should be held freely in the hands while playing, and a habit of pressing with the palm is unnecessary and only serves to retard facility of action. A good instruction Book is indispensable for information as to how to regulate the pressure, change from forte to piano, staccato to legato, directions as to reiteration of notes as well as the shake and other embellishments.

With a good instrument and instruction Book, much perseverance and a good ear, you may do a great deal unaided by a Teacher, but where the services of such are available, they will materially assist the advancement at first, and without some such assistance, you can scarcely hope to emulate a professional performer, although you may amuse yourself and others in a very creditable manner.

Many imagine that playing in correct time is only necessary for concerts, and that in playing solos a free time is excusable, and so much is the strict rule set at defiance by many amateur players, that half-bars continually slide away altogether, and this is noticed by those listeners who, if they do not play, can feel the effect of accent and rhythm. As the beauty of tone of the Concertina causes it to shine in solo passages and cadenzas the attention to rule cannot be too much recommended. Never let your instrument rock to and fro, as you could not in

[p.19]

that case be sure of the key under your finger. Attention to the study of style has a wonderful tendency to develope latent ability, and amateurs may rejoice in the possession of this expressive little instrument, affording enjoyment by the fireside in Winter, and in their gardens during the Summer. Surely as they say in starting a new Periodical “an acknowledged want is here supplied.” Let sweet melody float around impalpable and volatile as the scent of the violet. Hear what the Poet Milton says :—

To hear the lute well touch’d, or artful voice

Warble immortal notes and Tuscan air;

He who of those delights can judge and spare

To interpose them oft, is not unwise.

And in a treatise on Education, speaking of religious, martial, or civil ditties, the same Poet says “which, if wise men and prophets be not extremely out, have a great power over dispositions and manners, to smooth and make them gentle from rustic harshness and distempered passions.”

“Now good Cæsareo but that piece of Song: that old and antique song we had last night. Methought it did relieve my passion much.”

Twelfth Night.

“There let the pealing organ blow;

To the full voiced Choir below.

In service high and anthems clear,

As may with sweetness thro’ mine ear

Dissolve me into ecstacies,

And bring all Heaven before mine eyes.”

Milton.

“How did I weep in thy Hymns and Canticles touched to the quick by the Voices of thy sweet attuned Church! The

[p.20]

voices flowed into mine ears, and the Truth distilled into my heart whence the affections of my devotions overflowed and tears ran down, and happy was I therein.

St. Augustine.

I have endeavoured in the foregoing pages to make known an easy path which leads to a garden of delights; and in this attempt I have refrained from seeking assistance of any kiind, preferring to hazard the simple and unpolished statement of my own convictions without color or qualification. If I could be sure that the reading of this little book would induce a few persons desirous of enjoying Music, but looking upon its production as impossible in their own case, to suspend their judgment until they have re-considered the question, I should feel that my time and trouble had not been expended in vain. I shall be glad, if opportunity offers on some future occasion, to give a more copious explanation of the subject. For the present, dear Reader! Farewell!

[p.21]

Appendix.

From the South Hackney Correspondent, July 27, 1865.

A VOTE FOR THE CONCERTINA.

To the Editor,

Sir,—The musical season now terminating has presented the concert-loving portion of the public with a larger admixture of Concertina performances than usual, wherefore I trust that a remark of mine on the peculiarities of this instrument will be acceptable to some of your readers, especially as the English Concertina is making rapid strides in the favour of amateurs, notwithstanding the prejudice occasioned by the imperfections of its cousin-German. At the entertainments I have alluded to, a casual visitor cannot obtain a just idea of the suitability of the Concertina for home practice, while the proficient concertinist is disappointed to find that many beauties of the instrument do not receive justice at the hands of the artists, who frequently make high pitch and rapid articulation the chief characteristics of their performance to the exclusion of all murmurings soft and low of homely subjects such as

[p.22]

amateurs might emulate with a fair chance of success. The cantabile style with expression of tenderness is peculiarly suitable to the Concertina which when delicately handled possesses a quality of tone approaching the human voice as nearly as is possible for an artificial instrument, and the tremolo embellishment giving a gentle vibration to the notes, is pleasing when used with judgment; although, the best musicians advise players to be sparing in the use of embellishments of any kind, for when successfully practised the applause given to the performer is apt to betray him into the fatal error of intruding his favourite ornament wherever practicable to the great detriment of many beautiful melodies; sugar is good in its place, but most persons would object to taking it with roast beef.

A beautiful quality of tone is however not the only recommendation of a perfect Concertina; its portability and the position of the keys so convenient for harmony and rapidity of utterance, as well as the admirable blending of its sounds with those of other instruments, and its adaptability for interpreting every variety of composition from the solemn strains of Psalmody to the lively measures of the dance, all combine to make this unobtrusive instrument the most desirable one for those who have but little leisure for practice, while at the same time it affords ample scope for the talents of such artists as Guilio Regondi, George Case and Richard Blagrove, or those more recently displayed by the Mlles-Lachenal whose Concert was noticed in your number of the 17th June.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

TREMOLO–NON–TROPPO.

[p.23]

From the Scotsman, 23d October, 1865.

The great novelty in the programme was the concerted pieces, arranged for three and four Concertinas—the first occasion, we believe, in which such a combination has been heard in Edinburgh. The effect was exceedingly good, more especially in the operatic selections and the national airs. The first quartett, on themes from “Semiramide,” “Sonnambula,” and “Lucrezia Borgia,” played by the sisters Lachenal and Mr. Bridgman, was most satisfactory both as to its arrangement and performance. Mdlle. Marie Lachenal’s solo on airs from “Faust,” was also worthy of all praise for the tasteful and artistic manner in which it was rendered. Not less effective was the duet on subjects taken from “Les Huguenots,” played by Mdlles. Marie and Eugenie on treble and tenor concertinas. The trio on national melodies, as might have been expected met with an enthusiastic reception, and was re-demanded. Mdlles. Lachenal are unquestionably proficients on their respective instruments, and the musical public of Edinburgh are indebted to Mr. M'Laren for his enterprise in affording them an opportunity of hearing a performance both novel and interesting.

From the “Orchestra”, December 2nd, 1865.

Mr. Wm. Cawdell delivered last week a lecture at Dalston on “Domestic Music,” illustrating it on the Concertina. One of these illustrations—a selection from “Faust” arranged by Mr. Richard Blagrove—found favor with the audience, who, du reste, applauded Mr. Cawdell sufficiently to warrant the excellence of both lecture and performance.

[p.24]

[Blank.]

Have feedback on this article? Send it to the author.

Reprinted from the Concertina Library

http://www.concertina.com

© Copyright 2000– by Robert Gaskins

of the English Concertina …,

printed 1865 and 1866.

Contents

- A Short Account of the English Concertina …, W. Cawdell (1865)

- Introduction

- About the Transcription

- Transcription

Links to related documents

-

Cawdell’s ”Short Account“ 1865 printing [scanned]

Cawdell’s ”Short Account“ 1865 printing [scanned]

- by W. Cawdell

- … Its Uses and Capabilities, Facility of Acquirement, and Other Advantages. By An Amateur. W. Cawdell, 24, Dorchester Street, New North Road, N. Printed for the author by S.Johns, 7, Great St, Andrew Street, Broad Street, Bloomsbury, W.C., 1865. (Thought to be the first printing, prior to a second printing in 1866.)

- Posted 15 January 2005

- » read full document in PDF

-

Cawdell’s ”Short Account“ 1866 printing [scanned]

Cawdell’s ”Short Account“ 1866 printing [scanned]

- by W. Cawdell

- … Its Uses and Capabilities, Facility of Acquirement, and Other Advantages. By An Amateur. W. Cawdell, 24, Dorchester Street, New North Road, N. Printed for the author by S.Johns, 7, Great St, Andrew Street, Broad Street, Bloomsbury, W.C., 1866. (Thought to be a second printing after the 1865 printing.)

- Posted 15 January 2005

- » read full document in PDF

-

The Lachenal Sisters Visit Edinburgh, 1865–1866

The Lachenal Sisters Visit Edinburgh, 1865–1866

- by Robert Gaskins

- At Christmas of 1865–1866, three young daughters of the late Louis Lachenal gave a series of concerts in Edinburgh introducing “concerted music” played on treble, tenor, and bass concertinas. We think this was also exactly the period when Lachenal & Co. had lost their contract to manufacture concertinas for Wheatstone, making it important to publicize Lachenal’s own brand. Based on clippings from The Scotsman newspaper, Edinburgh, notices of concerts and reviews, October 1865 through January 1866.

- Posted 01 February 2005

- » read full article

Send this page to a friend.

This page was last changed | |

|

© Copyright 2000– by Robert Gaskins |